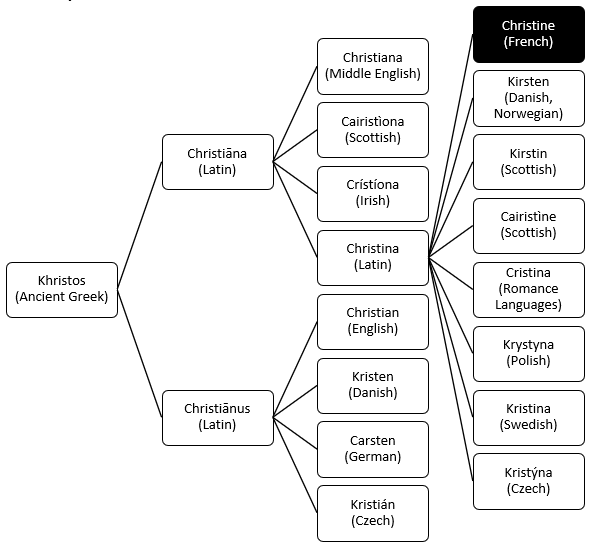

Christine and Christian, your name is really cool! It’s a Latin family name meaning “follower of Christ.”

This -iāna/-iānus suffix, which was used for members of a family or of a group having something to do with whatever the suffix is attached to, survives for us as the -ian suffix. Translating this idea into Elven languages is a little difficult, because the Elves don’t really have words for the “followers of an ideal/religion.” Indeed, the concept of religion would be very foreign to them.

Instead, I’m going to use words derived from the ancient root √NDIL, which describes love that is impersonal, more like scientific interest or fascination, and √NDUR, which describes love that is fidelity, loyalty, based in service. Tolkien described the difference between these concepts using the Quenya word for “tree – orne.”

“Thus an ornendil was one who ‘loved’ trees, and who (in addition no doubt to studying to ‘understand’ them) took an especial delight in them; but an ornendur was a tree-keep, a forester, a ‘woodsman’, a man concerned with trees as we might say ‘professionally’.”

While these words don’t truly capture the meaning of the original, it’s a close approximation.

When we have a name within a name, we have several approaches that we can take.

- Leave the name within the name untranslated. Instead, we’ll go by the pronunciation of the name in Elven languages. Tolkien provided us with Hristo in Quenya, so we can deduce that it’d be *Rhist in Sindarin.

- Translate the name within the name. Khristos in Ancient Greek means “Anointed One.” This comes from a ceremony popular in the Mediterranean that involved dripping holy oil on the head of the person being crowned king. Instead of translating this literally, which would be some variant of “oily head,” we’ll translate it as “king.”

Quenya

Let’s start with the Quenya-ization of Khristos, helpfully provided by Tolkien in a few of his translated prayers: Hristo.

Combine it with the Quenya suffixes –ndur and –ndil, which are gender neutral, and you get: Hristondur and Hristondil.

The masculine word for “king” is Aran and the gender-neutral word is Tár, which is often reduced to Tar in compound words.

Again, all of these are gender-neutral: Arandur, Tardur, Arandil, and Tardil.

Tar can be a little tricky because it’s also often used to indicate “high, royal, noble” as an adjective, which leaves to some lexical ambiguity. This means Tardur could be read as “royal servant” and Tardil could be read as “royal friend.”

It so happens that Arandur and Arandil are already used as words by Tolkien. Arandur is a King’s servant or steward. An Arandil is a royalist or friend of the king. Arandil is also a way to translate the word “Prince” as a political title. To the Elves and by their influence the Númenóreans, a prince or princess wasn’t defined by your family, but by your position of power. A prince or princess rules lands representing a king. The king has his stronghold and capitol city, and regions or cities that are far away still need governing. This is why Faramir is the Prince of Osgiliath while not being related to Aragorn.

When it comes to naming your Elves, the best versions are Tardil and Tardur, simply because Arandil and Arandur are terms for specific political offices, and Hristo, while Quenya in shape, isn’t actually a Quenya word.

Sindarin

When it comes to Sindarin words descending from √NDIL and √NDUR, we have a bit of a problem. We have a few names with descendants of √NDIL in them, like Gelennil and Gaerdil, but we have no evidence of anything descended from √NDUR in Sindarin. Instead, words for being a servant or attendant are based on roots like √SATAR “loyal, faithful” (Sadar/Sadron – “trustworthy follower”) √BEW “to serve” (Bŷr – servant) and √BORON “to endure” (Bôr/Boron – faithful man/vassal). Of these, Boron and Bôr occur in Sindarin names most often, but I’ll let you decide which version you prefer in the translation of your name.

Sindarin word-order in names is a little more flexible than it is in Quenya, so I can avoid some very weird sounding consonant combinations by putting the person doing the action first, as would be in the phrase “Vassal of *Rhist.”

Gender-neutral “Vassal of *Rhist”: Borrist, Borochrist, Byrrist, and Sadarrist.

Gender-neutral “*Rhist-vassal”: Rhissadar.

Masculine “*Rhist-vassal”: Rhissadron.

And lastly, but not least, “*Rhist-friend” and “Friend of *Rhist”: Rhistnil and Dilrist.

Next, let’s take the words for “King” (Aran, Âr and Taur) and add the same words:

Gender-neutral names using Dîl: Erennil, Ernil, and Tarnil.

Oh look, it’s Ernil, a word for “Prince”! Fancy seeing that here.

Gender-neutral names using Sadar: Arassadar, Arhadar, and Tarhadar.

Masculine names using Sadron: Arassadron, Arhadron, and Tarhadron.

Gender-neutral names using Bôr and Boron: Aramor, Arvor, Arvoron, Tarvor, and Tarvoron.

Gender-neutral names using Bŷr: Arvyr, Aramyr, and Tarvyr.

For your Middle-earth characters, I’d avoid *Rhist-based names because it’s not a Sindarin word. In some of the names, because of the mutation rules, it could be read as Rist, which is a word for the scar or impression left from cut. A weird thing to proudly proclaim in your name your loyalty to. The rest are fair-game, though I’d avoid Ernil as a personal name since it’s an official title.

![]()

Christine and Christian, I hope that you found this article interesting and useful!

If you’d like your name translated in this series, comment below and I’ll consider it for a future article!

Source:

Hanks, Patrick & Hodges, Flavia. A Dictionary of First Names Oxford University Press. 1990. pgs 63, 194, 195.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Nature of Middle-earth. Ed. Carl Hostetter. Harper Collins Publishers. 2021. pg 20.