Mary, your name is really cool! It’s an ancient name that has soared in popularity for thousands of years. It’s so old that we don’t exactly know its meaning. We have many, many possible meanings based on linguistic research.

There are two main theories. First is that it’s an old Hebrew name, and proposed meanings for it go from “a drop of the sea” which was later misread in Latin as “star of the sea” to “their rebellion” back to “bitter sea” and “Myrrh of the sea” around again to “great sorrow” and for good measure: “longed for a child” and so on. None of these are very likely, so it’s a very old name whose meaning has been lost or that is no longer decipherable.

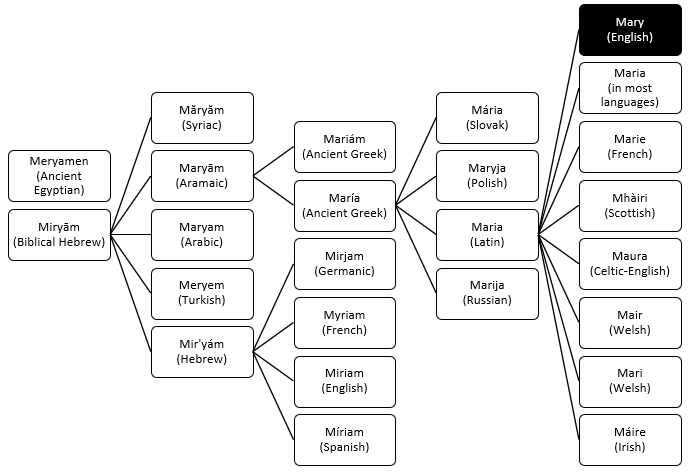

The other theory is that Miryām’s meaning is unknown because it’s a loan from Ancient Egyptian, where the names Meritamen (feminine) and Meryamen (masculine) appear as epithets for various royal figures. It should be noted that we know of these names from Hieroglyphic inscriptions, which only show consonants. This means that the vowels are less certain, and there are multiple possible pronunciations of it. The names were written MRY-T-YMN for women and MRY-YMN for men. The MRY means “beloved,” the T is a feminine name marker, and YMN means “Amun,” making the name “Beloved of Amun.” It looks like the feminizing affix was dropped in version of the name that was originally borrowed, but in Hebrew and all of its descendants after, it’s a feminine name. This does make sense because it appears first in Exodus as the name of Moses’ sister, and that she’d have an Egyptian loan-name like Moses does would be expected.

Since we don’t have a certain meaning, what translation should I base my Elvish translations on? I have several options:

- Leave untranslated, and just take the Greek version and make Elvish-ized pronunciations of María. Tolkien did this for Quenya, so it’s a pretty solid approach.

- Tell all you Marys to go find elvish names that are meaningful and important to you instead of depending on a translation, using my handy Name Lists to help you out.

- Try translating some of these sketchy interpretations. Of these, I’m using “Star of the Sea” because it was believed to be the translation for 1700 years, and the new, cool theory that it’s the Ancient Egyptian name MRY-YMN “Beloved of Amun” borrowed into Ancient Hebrew.

When it comes to translating MRY-YMN, we have the “name-within-a-name” problem. I’ll take two approaches to this:

- Leaving YMN untranslated, just Elvish-ize the pronunciation from the Late Egyptian ʔamōn.

- Taking the meaning of YMN “Hidden One” and translating that. “Dear-one of Hidden One” isn’t too clumsy to translate, so it’s doable.

Quenya

Let’s start with the Quenya-ization of the Ancient Greek María that Tolkien used, which is… just “María.” It is pronounced slightly differently (the acute accent in the Greek one indicates stress, while it indicates length in Quenya).

Our second approach is “Star of the Sea.” There are a few words for “star,” in Quenya, but the most generic is Elen. The word for “sea” is Ear. Put these together and you get: Earelen. If you want to make it explicitly feminine, you can add the suffix –e to make: Earelene.

Our third approach is “Beloved of ʔamōn.” If I try to translate this directly it’d mean something like “Beloved ʔamōn,” so instead I’ll translate this as “Friend of ʔamōn.” The Quenya-ization of ʔamōn would be *Amón.

For “Friend of…” we have three options: Nilde, Melde, and Serme. These three have different connotations, though they are all the feminine versions of these nouns.

- A Nilde is a woman who is devoted in their interest on a topic in a studious, distant way, like a scholar, scientist, or the follower of a specific deity. Nilde has a short, genderless version used as a suffix in names, –ndil.

- A Serme is a woman who has platonic affection for someone.

- A Melde is a woman who has deep love for the person, which might or might not be platonic.

Of these, Serme and Melde match the meaning the best, though Amondil is really tempting because it fits together so well.

Putting them together we get the following feminine names: Amosserme and Amommelde.

Next let’s try out “Hidden One” in place of Amón. Quenya has three different words for “hidden”: Halda (veiled), Muina (secret), and Nulla (obscured). Add a masculine name suffix and you get Haldo, Muino, and Nullo.

With Serme and Melde: Haldoserme, Haldomelde, Muinoserme, Muinomelde, Nulloserme, and Nullomelde.

When naming your Elven characters, I’d avoid the names with Amón in them and María because these don’t make sense in the Arda-context. I would add the genderless –ndil because it is shorter than the other options, making “Friend of Hidden-one” or “Star of the Sea” the meanings that you go with.

Genderless with –ndil: Haldondil, Muinondil, and Nullondil.

Sindarin

Starting with the Sindarin-ization of María, it’d be a little more complex. Tolkien liked to put these borrowings through the phonetic history of the target language to make a name that fits into the phonology of the language better. Maria would change like this to get to Sindarin: Maria>Meria>Meri>Meir>Mair. This makes the Sindarin version *Mair. The fact that this sounds so much like the Welsh version of Mary is no coincidence. Tolkien Was heavily inspired by Welsh’s phonetic development when he made Sindarin.

The next approach is “Star of the Sea.” The Sindarin words for “star” are Êl and Gail (usually appears as Gil in compound words). The word for “sea” is Gaer.

Put these together and you get: Elaer and Gilaer.

For the third approach, “Friend of ʔamōn,” the Sindarin-ized version is *Amun. We can combine it with two words for “friend,” Sêr and Mellon (which has the feminine version Meldis).

Combined we get the genderless names: Amusser and Amumellon.

Feminine version: Amumeldis.

With ʔamōn translated as “Hidden One,” we have a bunch of words in Sindarin: Hall (veiled), Doll (obscured), Thurin (secret), and Torn (secret). Combined with masculine name suffix, for ʔamōn we get Hallon, Dollon, Thurinor, and Tornor. But, I can’t think of any Sindarin names that have an agentive suffix inside them. So instead, I’m translating ʔamōn as “Tornas – Secret.”

All these combined and we get: Tornasser and Tornasmellon.

Feminine versions: Tornasmeldis.

In a Middle-earth context rather than a “us in our world trying to translate our names” context, *Mair sounds like the fanmade Sindarin cognate of Mirya (precious) in Quenya. So, you could use it on its own, though adjectives usually have a name suffix added to them, but it isn’t necessary.

Amun isn’t a word in Sindarin, so those names aren’t useable for your characters, but the “friend of secret” names work. We could add the looser gender-neutral translation Tornasdil.

![]()

Mary, I hope that you found this article interesting and useful!

If you’d like your name translated in this series, comment below and I’ll consider it for a future article!

Sources:

Hanks, Patrick & Hodges, Flavia. A Dictionary of First Names Oxford University Press. 1990. pgs 223-224, 228-229, 239.

Hart, George. The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. United Kingdom, Routledge, 2005. pg 14.

Knight, Kevin. New Advent “The Name of Mary” 2020.

Wiktionary “מרים” Last Edited: April 20th, 2021.

Wiktionary “mry-jmn” Last Edited: December 16th, 2020.