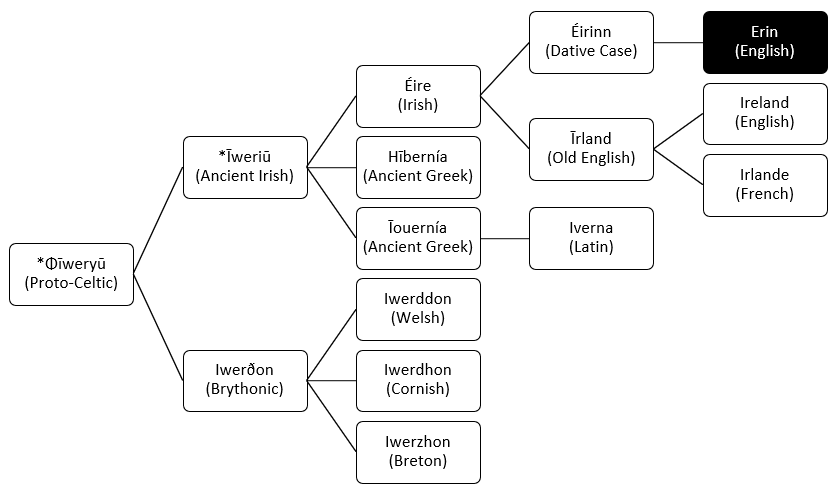

Erin, your name is really cool! It’s an Irish name meaning “to/for Ireland.” As a personal name it pops up in the 20th century, thus I’ve charted its development as the name of Ireland.

“Dative Case” is a fancy linguistic term for nouns being used in a sentence, where the action is directed “to [fill in noun here]” or “for [fill in noun here].” In many languages, Irish included, this isn’t done with prepositions as it is in English, but with special suffixes called “case endings.”

This is one of those “name within a name” cases. This means we have a couple choices:

- Translate the name-within-a-name too. The name of Ireland itself descends from Proto-Indo-European words having to do with “fertile, fat, milk” so we can guess that it means some variant of “Fertile Land.” This would make names meaning “to/for the fertile land,” which isn’t a weird or confusing meaning for once!

- Leave the name untranslated. We’d Elvish-ized the pronunciation of Ireland and make it fit into the name that way.

Quenya

Let’s tackle translating “Ireland” into Quenya first. The best way to translate “fertile” is with a reference to the goddess of growing things herself, Yavanna “the Fruit-Giver.” To make this name, I’m combining “Yáve – fruit” and the land-name suffix “-ien.” This makes the name Yávien. Then we just add the dative case ending and we get Yávienden – To/For Fruitland.”

Next, the untranslated version. Here, we can have some fun! In The Book of Lost Tales (1 & 2) we see some of Tolkien’s really early stories about Arda, written in his 20’s. In this time period, he was already deep into the making of the languages that would become Sindarin and Quenya, though at this time they were called “Gnomish” and “Qenya” (no U after the Q) and both languages would change radically throughout his life. In this early period, he decided that Arda was a place that you could get to from England. His Self-insert character goes there, gets an Elvish name (the first occurrence of “Elf-friend”!) and long story short, Tolkien made Qenya and Gnomish words for “Ireland.”

The Qenya word is Íwerin/Íverin. Tolkien got this word from the Latin “Iverna,” though he likely was influenced by the Welsh word “Iwerddon” as well. He’s broken these into Íver/Íwer + place name suffix. Looking at the phonology, this word still works great for Tolkien’s later Quenya. Thus, “to/for Íverin” is Íverinden.

As a place name, Yávien is great! But for a character’s name, not so much. Íverin doesn’t sound like any Quenya word either, so it’s a nonsense name. For your Elven characters, I’d suggest going for “fruitful” as the meaning. To make this, you take Yáve – fruit and –inqua – full of, which makes the adjective Yávinqua. For a feminine name, Yávinque.

Sindarin

I’m going to take the same approach to translating “Ireland” that I did in Quenya. We’re not directly given a word for “fruit,” but we can deduce it from the word for “harvest – Iavas.” The word is Iâf. Then we can add a place name suffix to it. I’m going to do “-an” as in “Rochan.” Putting these together makes Iavan. Then, to make the Dative case in Sindarin, you use the preposition “an – to/for.” You can include prepositions in words in Sindarin, which makes Aniavan or the phrase “An Iavan.”

Back when Sindarin was Gnomish, the word Tolkien made for “Ireland” was Aivrin/Aivrien/Iwrien/Ivrien. The ones with AI- don’t work phonetically in later Sindarin. The diphthong AI can only exist in the final syllable. The final two have more promise, but one still misses the mark. W didn’t become V in Sindarin. That leaves Iwrien. This one works surprisingly well. The –ien is still used in place names (plural of iand, meaning “expanse”). Losing syllables by cutting out a vowel is pretty common in Sindarin, so going from Íwer to Iwr– isn’t impossible.

Now that we’ve chosen Iwrien, we add the preposition “to/for,” making An Iwrien or Aniwrien.

As with Quenya, these names are pretty nonsensical for Middle-earth characters. I suggest dropping everything but the “fruitful” angle. The suffix for “-full” in Sindarin is “-eb.” Combine it with the noun Iâf and you’d get Iaveb “fruitful.” To make it feminine, you’d add a few different name suffixes, making Iavebeth, Iavebel, and Ievebil.

![]()

Erin, I hope that you found this article fun and interesting!

If you’d like your name translated in this series, comment below and I’ll consider it for a future article!

Sources:

Hanks, Patrick & Hodges, Flavia. A Dictionary of First Names Oxford University Press. 1990. pg 106.

Wiktionary, “Reconstruction:Proto-Celtic/Φīweryū” Last edited: March 6th, 2021.